Your cart is currently empty!

Beyond the Numbers, Ethnography: Here’s an Urban Method That Will Serve You (and It’s Not Perception Surveys)

I once heard that everything that cannot be measured does not exist. This somewhat rigid and categorical definition may deny multiple activities and dynamics that modify the places where we live. Therefore, this article seeks to introduce a sensitive method to observe things that are generally difficult to quantify.

In recent times, measurement and evaluation tools for the use of public space have gained popularity among local governments, consulting firms, and organizations focused on urban management and projects. Abundant manuals and guides have flooded specialized networks in urban planning, especially since the release of the valuable kit for studying public space created by the Gehl Institute.

However, most of these tools focus on quantitative aspects and parameters: people flows, the number of elements, minutes of stay, among others. On the other hand, the qualitative tools that have gained popularity focus on investigating individuals’ perceptions through surveys or interviews.

The power of multidisciplinarity can provide us with a series of extraordinary resources to complement our work and better understand what happens in urban space. So, I present a well-known method in the academic field, originating from the world of Anthropology: ethnography and participant observations. The technique involves observing a space over a period of time, identifying the various activities that people engage in there, how they interact with each other, and what behavioral patterns they exhibit.

Despite its apparent simplicity, the real value of the technique is manifested when it is systematized and organized. Through a colleague, I had the opportunity to meet anthropologist Rosana Guber, who has extensive experience in ethnographies and has developed an observation technique called PATE, which she outlines in her book “La Etnografía, método, campo y reflexividad” (2011). The method focuses on four categories to observe what happens in a specific space: People, Activities, Time, and Space.

Inspired by this method, I have added specific parameters to each category, creating my own method for my research project on migration and public space, recently concluded in Sicily, Italy.

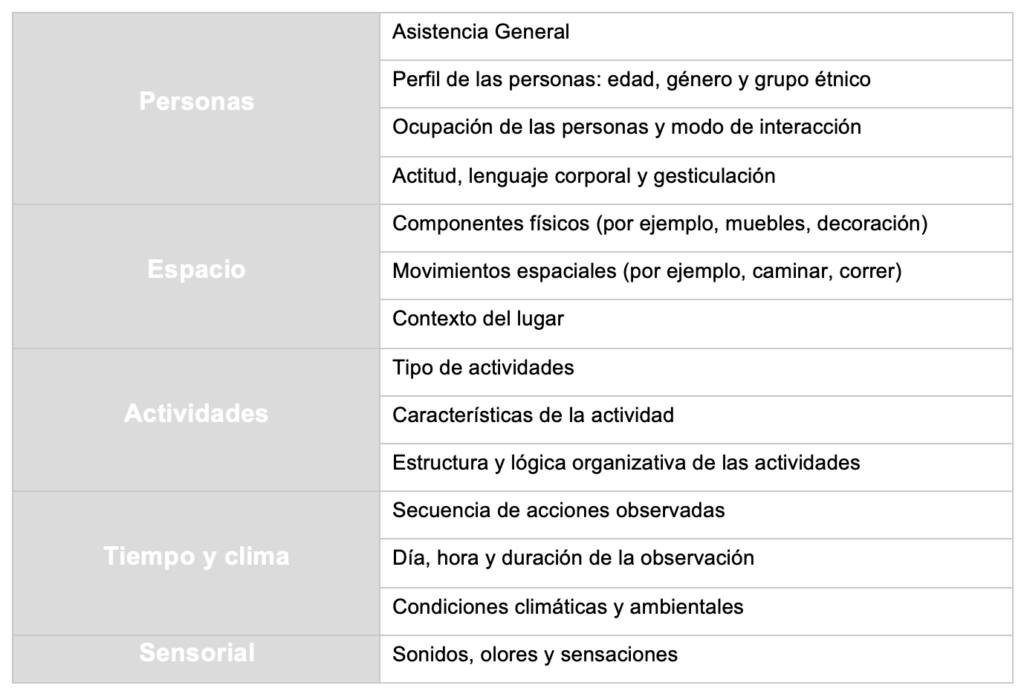

Figure 1: Categories and subcategories to observe

The “People” section delves into the diversity and dynamics of individuals in the observed area: sellers, customers, spectators, passersby, and others. It covers their demographic profiles, occupations, interactions, attitudes, body language, and other behavioral aspects.

For example, in my research, most of the identified people were adult men, potential buyers who observed products for sale and interacted amiably with others in Sicilian dialect and other languages. No confrontational attitudes, arguments, or fights were identified.

“Space” explores the physicality and layout of the place, examining the interaction of fixed and movable elements. This includes the tangible components that make up the area: tables, blankets, cars, buildings, among others, and the less tangible but equally crucial aspects such as spatial organization and types of movements. For example, do most people move on foot, by bicycle, or are there vehicles?

“Activities” reflects perceptions of the range and nature of actions taking place in the observed area, such as commercial or recreational activities, among others. It also takes into account the structures of these activities, their characteristics, and the patterns they form, including how many people are involved, whether they are horizontal or vertical.

“Time and Weather” examine how the temporal dimension shapes and influences the rhythms, flows, and dynamics of the observed area, including the sequence of actions, the pace of activities, movements influenced by external factors such as weather and the time of day.

“Sensorial,” an additional category, seeks to incorporate the senses into the observation of the area, recognizing that the city is not just what we see but also what we feel and perceive. It is the most subjective section of observation, focusing on smells, sounds, and the emotional and psychological responses these sensory stimuli can evoke.

Now, how is such an observation done?

Step 1: Selection of Urban Spaces

– Identification of Areas: Choose one or several urban spaces to analyze, ensuring that these selections align with the objectives of your study.

– Preliminary Evaluation: Visit the identified places beforehand, providing a basis for deciding on the specific times and methods for observation.

Step 2: Time Planning

– Establishment of Days and Hours: Determine the precise days and times for observations, taking into account the particularities and specific dynamics of each space.

– Temporal Consistency: Strive to carry out observations at consistent times, such as every Tuesday and Saturday, in both morning (10:00-11:00 am) and afternoon (5:00-6:00 pm) hours, as well as nighttime, allowing for comparisons across various temporal contexts. This will depend entirely on your research.

Step 3: Positioning Strategy

– Location: Position yourself at a point that offers a broad view of what is happening. You can sit or stand; the important thing is that you are comfortable and do not disturb or inconvenience the people in the area.

– Spatial Coherence: Ensure that all observations are made from the same location, facilitating data comparison between different observed moments.

Step 4: Data Collection

– Use of Analog or Digital Tools:

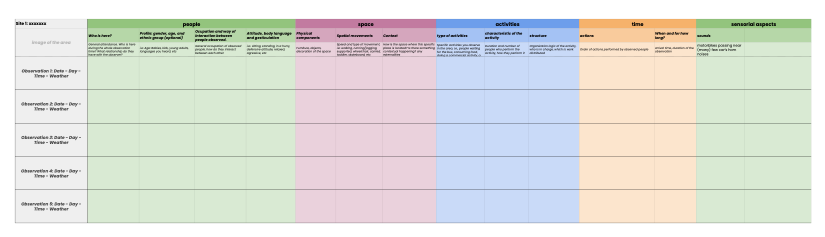

You will use the categories and subcategories (see Figure 1) presented earlier to collect information. You can do this by hand in a notebook or digitally. I suggest the latter since you can save a lot of processing time directly from a mobile phone. For this purpose, I have created a Google Spreadsheet template that you can open on your mobile and fill out live during the observation. The left side of the spreadsheet contains the observation day, while the header displays the main and secondary categories. While respecting the observation day, you will complete the different observation categories in list format or narratively, whichever is more comfortable for you. You can do it in order or as you observe; it is not a linear process because what happens in the area is dynamic and will change during the observation. The important thing is to take a few minutes at the end to review all the loaded information.

Figure 3: Digital spreadsheet for real-time data entry on your mobile phone

In my case, I decided to do it digitally as taking notes in a notebook generated tensions in some street vendors, creating what Guber (2011) calls “suspicion of espionage.” This could place the researcher as a threatening emissary of some dominant power structure outside the community. The possibility of using your phone or a notebook will depend entirely on the place you are observing, which you can define through prior visits and site testing.

Step 5: Data Analysis

Once all the information has been collected, I suggest using qualitative data analysis software like MaxQDA to detect behavior patterns and draw conclusions about how and who uses the observed space. Creating labels and defining subthemes in this software will allow you to reach conclusions more quickly. It is essential to be able to compare the various observations with each other and with external factors.

You can also process the information more simply by comparing the observed days and writing conclusions. Another very useful option is to process the collected information with artificial intelligence software, which is included in some data analysis software. Be very careful with the privacy conditions that these platforms offer since you are handling sensitive data.

Ethical Considerations

In the implementation of urban ethnography, it is imperative to address ethical issues and the handling of sensitive data with integrity and responsibility. Respect for the privacy of individuals observed in public spaces is crucial, and as researchers, we must ensure the protection of their identity in any communication or publication resulting

from the study. Furthermore, an approach that focuses on producing benefits to the community while avoiding harm should be taken. Transparency and clear communication about the objectives, methods, and findings of the research, allowing for information flow and potential benefits back to the observed communities, should also be central elements in the ethical practice of studying urban spaces.

Final Considerations

Participant observations based on the PATE method (Guber, 2011) help us understand urban spaces more deeply, providing a more human and empathetic view of urbanism and the everyday realities of its inhabitants. I believe that this methodology should be complemented with others such as detailed interviews and spatial mapping to gain a profound understanding of the community and the space it inhabits.

In my research project on migration and public space in Sicily, this methodology has been crucial in unraveling the complexities and subtleties of how migrants and other actors relate, negotiate, and shape the public spaces they inhabit. In future installments, I will share more about the specific conclusions and emerging narratives that this rich methodology has allowed us to discover.

If you have any questions about how to use this tool, please write them in the comments!

References: Guber, R. (2011). La Etnografía. método, campo y reflexividad. Siglo Veintiuno”

Post a comment