Civic Design: Circular Process

Summary

This article aims to contribute to the reflection on the new practices that are transforming the professional and institutional approach to the activation and management of collective intelligence processes that involve different actors in a territory and that we are defining as civic design (Di Siena, 2015).

Collaboration and collective intelligence processes represent an emerging practice where there is a renewed capacity of the inhabitants of a territory to achieve processes of transformation and improvement of their environment in complementarity and collaboration with the action of the public sector, the private sector or the third sector (Peña-López, 2019).

Civic design allows us to activate processes of collective intelligence by reinforcing the capacity of the inhabitants of a territory to relate to each other and become involved in different spheres and with different intensities in processes of transformation and improvement of their environment.

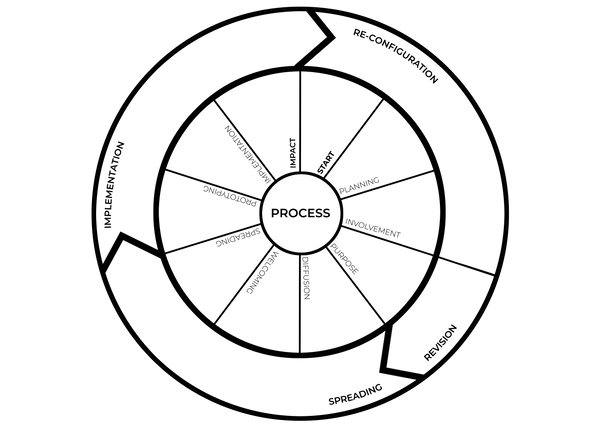

This article presents a tool called “Circular Process” capable of discerning and highlighting the main actions and dynamics that make up a Collective Intelligence activation process.

The article describes this methodological pattern using a case study that has involved a very intense reflection on how to involve a high number of local actors while maintaining a good relationship with the expectations of the public administration and local communities.

Context

The ability to think of ourselves as a network opens up a new sphere for collective construction that we cannot ascribe to any of those known to date (Castells, 2010).

Collaboration and collective intelligence processes represent an emerging practice where there is a renewed capacity of the inhabitants of a territory to achieve processes of transformation and improvement of their environment in complementarity and collaboration with the action of the public sector, the private sector or the third sector (Peña-López, 2019).

To activate this type of processes we need a new framework for action and new forms of articulation that activate collaboration between actors who are not used to collaborating (Chautón, Di Siena, 2019).

I want to advance the reflections that have finally brought the academy closer to professional practice and citizen activism (Corsin 2017). Two important things are happening, on the one hand the academy recognises a new experimental practice that activates citizen participation without the need for strict and pre-defined institutional frameworks (Lafuente, Estalella, Corsin, 2012), on the other hand activism recognises the usefulness of practitioners in its relationship with the institutional (Corsin 2017).

This debate is joined by a new perspective that is activated by different cases of actors who, from within public institutions, are activating innovative processes of openness towards the outside, towards citizens and other actors in the territory, as is amply described in the book “Opening institutions from within [Hacking Inside Black Book]” published by the LAAAB of Aragon (Spain).

I want to describe how we are changing the way we understand collaborative processes by proposing collective, multi-actor and transdisciplinary practices, with the capacity to structure processes of collective intelligence that are recognisable and have an impact on the territory.

Hypothesis

We are witnessing the emergence of a practice that we can call Civic Design, which does not yet have much academic literature and attention from research, but does have a lot of attention from professional practice. This practice shifts the focus from the design of solutions to the design of processes that can lead us to define a solution thanks to the involvement of a significant number of actors in the territory.

In support of studies on this new professional and institutional practice, such as the work of Camilla Buchanan, Mariana Amatullo and Eduardo Staszowski on the practice of New York City, I propose a tool capable of extracting and highlighting the main actions and dynamics that make up a process of activating Collective Intelligence.

With this article I want to demonstrate how this tool manages to describe the path and the dynamics that allow us to get from an initial context in which a challenge or a problem of the territory is posed, to a final proposal through collective, multi-actor and transdisciplinary practices, with the capacity to structure recognisable collective intelligence processes and therefore its usefulness as a reference for civic design.

Methodology

This article is the result of a much broader research that I was developing within the scope of the PhD programme “Sustainability and Regeneration” of the Polytechnic University of Madrid; it is born then in the context of a research of more than 10 years, developed from an iterative approach, where each stage and method has been developed from the findings of the previous stage and method.

The trigger for the final approach has been a process of analysis and review, parallel to my research activity, of my 15 years of professional experience, which I have initiated spontaneously, with the aim of verifying the existence or less of a methodological pattern capable of describing my own way of working and the projects or interventions in which I have been involved, mostly of a collaborative type.

As a consequence, I take advantage of the research to describe the potential of a new methodological approach related to territorial transformation actions activated and developed from the involvement of multiple local and global actors.

In this way I put professional research and experimentation together with the practice of academic research in a space of synergy. This translates into the sequential application of two actions. On the one hand a deductive work with which I come to define a methodology of professional work on the basis of a long and wide activity of experimentation made possible by dozens of practical cases, and on the other hand a research work focused on the comparison of three concrete cases in which we can recognise the methodological pattern of my professional practice.

From a work of analysis I have moved on to a work of synthesis that has allowed me to define a methodological pattern common to all the case studies. This translates into the possibility of approaching a comparative analysis, which in addition to having the objective of finding patterns for the validation of my initial hypothesis, allows us to demonstrate the emergence of the practice that we have called Civic Design, which, starting from different situations and contexts, manages to activate the dynamics of Situated Collective Intelligence. This work of synthesis is accessible on a website that I have created http://civicdesignmethod.com where it is possible to download the White Paper of the Civic Design Method (Di Siena, 2019).

In this article I want to focus on one of the most relevant aspects of the Civic Design approach, which corresponds to the possibility of designing a process rather than a specific solution. A key part of the methodological pattern developed with my research has to do with the definition of basic tools that help us in the practice of design and in this case in the practice of designing a process, which in itself is conceived with the objective of activating a Collective Intelligence that allows the different actors present in a territory to collaborate to reach a result with a high degree of consensus. To this end, I have defined a working scheme that I call the Circular Process for Civic Design.

Using a case study in which I have personally participated, we will see how the Circular Process for Civic Design scheme succeeds in describing and understanding the development of a very complex design process.

Case study: Dreamhamar

Dreamhamar is a proposal developed by the Madrid-based architecture and urban planning studio Ecosistema Urbano. It is a participatory and networked design process aimed at redesigning the public space of Stortorget Square in the city of Hamar in Norway. The first version of this process was designed as a proposal for a public competition in 2010. Once selected as the winning proposal, it was carried out during 2011 and 2012 during which the citizens of the city of Hamar have been able to participate in the collective reflection process that culminated in a new design of the square. This is a pioneering approach in the field of the configuration of new public spaces or the transformation of existing ones, due to its commitment to an open and multifaceted process structured around a very broad programme of workshops, conferences, urban actions, communication tools and participation.

The development of this project has involved a very intense reflection on how to involve a large number of local actors while maintaining a good relationship with the expectations of the public administration and local communities. All of this in a territorial and cultural context that was new for the professionals who led it.

We can describe the Dreamhamar process in these 10 phases: 1. Start: Development of a proposal for the competition developed from Spain; 2. Planning: Definition of the activities that structure the design process; 3. Involvement of local and local communities and stakeholders; 4. Purpose: review of the initial purpose and reconfiguration of the equipment;

5. Dissemination: promotion of the process to local communities; 6. Welcome Practices for all those who wish to collaborate; 7. Deployment of programmes of workshops and collective activities; 8. Prototyping: full-scale testing on the square; 9. Implementation of the inputs for a preliminary project of the square; 10. Results and impact.

1. Beginning: Development of a proposal for the competition developed from Spain

The beginning of this project corresponds to the decision to enter the competition organised by the municipality of Hamar in Norway and the definition of a first working team. Due to its experimental nature related to art, the competition required the formation of a mixed team that included at least one architect and one artist. Our team consisted of several professionals, mainly architects, and an artist.

The object of the competition was the development of an artwork in view of a process of redefinition of Hamar’s Stortorget square. The competition brief also specified a number of objectives that are not usually directly associated with an artistic intervention: the artwork should have been able to give back identity and visibility to the square, but also to the whole city and the local community, and should have contributed to generate a greater capacity to retain young people who usually migrate to bigger cities.

2. Planning: Definition of the activities that structure the design process.

We were clear about the complexity of the proposal, so we focused on defining a very detailed process that includes different cycles and activities that we considered necessary to involve the different local actors in order to reach a final design for the square. The first proposal submitted to the competition did not yet directly address the possibility of a redesign of the square. In order to fit in with the competition brief, we limited ourselves to presenting a process that would allow us to create 6 works of art developed in collaboration with the public as a test to then arrive at a final proposal.

As a starting point to connect with the territory, we defined the work with schools and from there, after field work, we would continue to connect with local organisations, also with the support of the information that the public administration would pass on to us.

3. Involvement of local and global communities and stakeholders

We started with the planned actions. We focused on working with schools and high schools to generate the first link with the territory and local communities. We connected with a large number of parents in an informal way, opening the doors to subsequent activities organised with different local entities. We generated, little by little and in an organised way, a trust-building process that proved to be key to the continuity of the process.

The involvement plan foresaw the meeting with local actors based on the recommendations that could be made by the town council technicians and the conversations with the parents of the children and adolescents of the schools where the first activities were programmed.

For this reason, for several days we held meetings with all the political groups and all the representatives of the municipal assembly explaining the great opportunities of the project and clarifying any doubts they might have. This work proved to be enormously valuable in order to activate and involve the organisations we had already met with in order to gain their support. Moreover, this work and the vote of the citizens’ assembly also generated a favourable context of support for a project that was in any case very experimental.

This was also the reconfiguration phase of the team. Once proclaimed winners, the team was structured in two groups, one that stayed in the city of Hamar maintaining a constant relationship with the public administration and local communities, and another that stayed in Madrid to provide support. To complete the configuration of the team, local and international experts were also selected for each of the six thematic axes that structured the whole process.

To activate a glocal dimension with interaction between the local and the global, we introduced several external elements such as a network of universities and a programme of laboratories developed directly online that would have the role of enriching the whole local on-site process with new proposals. We were concerned with generating a network of people and communities of students and researchers from different parts of the world who could participate in the process and interact with the inhabitants to promote a greater openness of the collective imagination about the present and the future of the square.

4. Revision of the initial purpose and reconfiguration of the equipment.

Before we could start the whole process, it was necessary to negotiate with the public administration about the possibility of working more directly with the redefinition of the square and the duration of the process. We finally got the support of the city council for a process of redefinition of the square based on the experimentation of six ephemeral works of art, but we had to greatly reduce the duration of the process from a year and a half to 8 months, with the commitment to deliver intermediate reports in which the results achieved would be evidenced.

Once the winners were proclaimed, two people from the team moved directly to the city of Hamar, while others travelled to offer support at the most intense moments. The team was structured in two groups, one that stayed in the city of Hamar maintaining a constant relationship with the public administration and local communities and another that stayed in support from Madrid.

The local team was composed of two architects and other local professional figures. We hired a journalist who was in charge of communication and relations with local newspapers and four educators and mediators who accompanied us in our relations with different organisations and citizens. These mediators also had the task of coordinating workshops and collective activities.

The Madrid team was in charge of all the technical support and coordination of two important parts. The infrastructure and activities of the workshops and online productions (the Digital Lab) and then all the production of reports and urban design that were produced throughout the process until the final delivery.

To complete the configuration of the team, local and international experts were also selected for each of the six thematic axes that structured the whole process.

5. Dissemination: promoting the process to local communities

In this phase, we focused on organising communication and strategies to publicise the process. We have previously defined the graphic languages and the focus of the first activities that generate the first impact on citizens.

We finally decided to start the process with a festive event. We invited the Madrid graffiti collective Boa Mistura who intervened on half of the square with a striking painting that replicated the geometric motifs and colours typical of Norwegian culture, directly on the ground. This was accompanied by a festive event that was sufficiently eye-catching for the local newspapers to come and publish the news, publicising the start of the process.

It was also the moment of activation and dissemination of the website and the different channels activated on social networks.

6. Organisation of the Welcome Practices for all those who wish to collaborate.

Once the infrastructure was in place and after the numerous interviews with local actors and the first launching event of the process, the local team organised itself to be able to receive and welcome people and organisations that wanted to join the process or even to propose activities.

7. Deployment of the workshop and group activity programmes

With the infrastructure activated, the purpose redefined and the team established in the city, the roll-out of all programming begins. The process was structured around different types of activities:

1) “The Cultural Racksuck” a programme of activities with 12 local high schools involving more than 1000 children and young people.

2) Two online workshops, one focusing on public space and citizenship and the other on tactical urbanism.

3) Programming of six thematic weeks. Each of these thematic weeks included the invitation of an international expert and a local expert (community activator) who stayed one week to support the process and gave a lecture and a thematic workshop. The themes were: Citizenship, Environment, Technology, Seasonal Strategy, Activities, Future.

4) In parallel to these activities, six interventions were programmed in the square, starting with the opening intervention with the Boa Mistura collective. The following interventions had a very important production in terms of logistical organisation and communication.

8. Prototyping: full-scale testing on the site

Different prototypes and interventions were made in the square, all at low cost and with great visual impact, reusing materials and thinking carefully about the management of all phases: before, during and after. Of course, these were temporary interventions, but we were careful to avoid seeing them as a poor reproduction of reality, but rather as an opportunity to use the square in a different way, even if only for a few days, and to expand the imagination of the citizens.

These direct experiments in the square facilitated the synthesis and proposal work developed by the technical team with the final design proposals for the square.

9. Implementation of the inputs for a preliminary project of the square.

After having carried out most of the workshops and activities with the different communities and taking advantage of the tests developed directly in the square, the technical team focused on the definition of a first preliminary project proposal. This proposal has taken into account the inputs obtained in the different activities, proposing a configuration of the spaces of the square thinking not only in the formal part but also in the opportunity to include in the design a vision of different activities and dynamics thought from the direct involvement of the citizens and their capacity for self-organisation.

Finally, the elements of the project that foresaw a greater connection with the citizens were eliminated in the execution project developed by another architectural studio that took over from the work developed by the studio Ecosistema Urbano, of which I was also a member.

10. Outcomes and impact

The preliminary project is presented to the public administration and in some public sessions with the neighbours to take into account the final comments of the local communities. Then, with the agreement of the public administration, the technical team proceeds to define the final project.

Undoubtedly the final result and the greatest element of impact is to have managed to radically transform the imaginary of and the use that citizens make of the square, which has ceased to be a car park and has managed to become an important meeting place for local communities.

Situated Collective Intelligence

Collective Intelligence reminds us that there are other ways of working collectively beyond the democratic and assembly models. The most important point is in its creative and productive approach. The essence is that it is not about making decisions but about generating proposals and new spaces of opportunity: to avoid generating those dynamics that divide people into sides, majorities and minorities, always working from the confluence (Di Siena, 2017).

The results of any process or context of Collective Intelligence are not developed from the simple sum of the contribution or thinking of each actor involved, but from the result of the interaction, debate and collaborative work that is developed among all (Rey, 2017).

In short, we are talking about dynamics where the inhabitants of a territory in constant connection develop mechanisms for transformation and management that go beyond the old structures based on representation, becoming more efficient, more open and more transparent (Ruiz, 2019).

This is why in the case of processes related to territory we need to underline that we are talking about a situated collective intelligence, i.e. strongly conditioned, reinforced and developed from the territory, involving its actors, its cultural, economic, political and geographical conditions.

Civic Design

In my research work on the processes, spaces and practices that enable the activation of Collective Intelligence dynamics, I refer to Civic Design. This concept is in an emerging state of definition, which does not yet have an extensive literature. From my professional experience (practitioner) I understand Civic Design as the set of dynamics and strategies that enable the activation of Collective Intelligence processes with an impact on the Territory.

I consider that Civic Design focuses on civic projects, i.e. projects related to citizenship understood as a collective that inhabits a territory; it is based on multidisciplinarity and on the enhancement of situated knowledge, where the professional is placed at the service of the collective from a perspective of collaboration and facilitation of processes.

From the Civic Design approach we understand that professionals make our experience and knowledge available, not so much to generate a response to a problem or to generate a direct solution, but by placing ourselves at the service of a community or a specific territory, in order to promote the activation of an environment of exchange and collaboration in which local actors interact to generate a process of Collective Intelligence, through which we then arrive at concrete proposals.

Circular Process

The circular process represents one of the tools resulting from the synthesis work developed from the analysis of my experience as a practitioner. It leads us to a reflection focused on defining the different phases of a Civic Design process. It offers a definition and understanding of the circular process that can help us to activate Collective Intelligence, specifically connected to or developed from a territory.

It is structured in 10 phases, in a circular sequence that can be replicated and restarted at any of its points. We understand that learning and improvements in any process can be produced through a theoretical research process (thinking/configuring) but also through the execution or production process itself (doing/implementing): situations or unforeseen conditions determine the need to act differently from what was planned (situate/deploy), generating a discovery, a new learning.

Below is the presentation of the 10 phases:

1. Beginning

Creation of the initial team. Definition of the initial objective and purpose of the process.

2. Planning

Preliminary analysis to identify local communities and actors. Definition of the different phases and objectives of the process.

3. Involvement

Involve the communities and agents of the territory. Incorporation of professionals promoting transdisciplinarity and glocality. Synchronisation of the entire team and activation of protocols and governance of collaborative, open and transparent work.

4. Purpose

Review of the initial purpose involving the whole team and local communities and actors. Develop a narrative describing the objective of the process, its stages and methodology.

5. Dissemination

Communication of the start of the process in different platforms, media and formats.

6. Welcome

Activation of the dynamics and mechanisms to welcome all interested persons into the process.

7. Deployment

Activating sets of dynamics and devices to activate collective intelligence

8. Prototyping

Creation and production of low-cost prototypes. Direct experimentation with one of the parts that define the final project in order to test the effective capacity to achieve results, so that when it comes to scaling up, there are fewer problems and failures.

9. Implementation

Move on to the implementation of what was proposed in the previous phases. Scale up the tests of the prototyping phase.

10. Impact

Close the cycle to open another one. After the implementation of the proposal, we look for ways in which it can be replicated, sustained or connected with other realities or processes so that it continues to generate positive effects and regenerate itself.

Conclusions

As we have seen, Civic Design proposes to arrive at the expected solutions through processes or methods, enabling relationships and strategies based on the collaboration of many actors located in their territories. It is not a collective deliberation approach but a process facilitated by professionals who put their knowledge at the service of a community. The main challenge for the success of this type of process lies in the ability to define the development cycles and the different sequences that lead from one phase to the next while keeping the interest and support of local communities alive.

The Civic Designer designs the process necessary to promote the activation of Situated Collective Intelligence by defining how the actors in the territory will interact, where they will do so, with what type of activities and how often; he/she designs the dynamics and defines the technologies that will be used throughout the process.

The application of the Circular Process to the Dreamahamar case study helps us to structure and understand the development of a design process that has involved many actors who were not coordinated among themselves and who were not necessarily even interested in the present and future of the square. This kind of approach helps us to determine a series of strategies where action, communication, experimentation and co-design activate local communities from a collaborative perspective capable of valorising the situated knowledge of all the actors. All this is possible thanks to the design of a process and the capacity of designers to play their role as facilitators at the same time.

This type of professional approach is currently in a phase of emergence and is still dependent on a lot of experimentation, which in many cases is in fact pure improvisation. This is why it is indispensable to analyse the projects that managed to achieve concrete results under the lens of a recognisable structure. The circular process, as we have seen, offers this indispensable support to analyse successful case studies and to become active in defining the design of new interventions that want to activate a collective intelligence in the (situated) territory.

Bibliography

Bawuens, M. 2012, “Blueprint for P2P Society: The Partner State & Ethical Economy”, Shareable, viewed 21 May 2019,

<https://www.shareable.net/blueprint-for-p2p-society-the-partner-state-ethical-economy/>.

Buchanan, C., Amatullo, M., Staszowski, E., “Building the Civic Design Field in New York City”. Diseña, [S.l.], n. 14, p. 158-183, Jan. 2019. ISSN 2452-4298, viewed 05 june 2019

<http://revistadisena.uc.cl/index.php/Disena/article/view/165>.

Chautón, A., Di Siena, D., 2019, Civic Transitions, viewed 28 march 2019

<https://medium.com/@civictransitions/civic-transitions-9acbc11c2d6c>.

Deleuze, G. & Guattari, F. (1980): Mil mesetas, Valencia, Pre-Textos, 1988.

Desis Network, 2013, Public & Collaborative: Exploring the Intersection of Design, Social Innovation and Public Policy; edited by Eduardo Staszwoski. ISBN: 978-0-615-82598-4, viewed 21 april 2019

<https://www.desisnetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/DESIS_PUBLIColab-Book.pdf>.

Di Siena, D., 2019, Civic Design Method Whitepaper, viewed 28 march 2019

<http://civicdesignmethod.com>.

LAW, J., 1986, “On power and its Tactics: a View from the Sociology of Science”, The Sociologocial Review, 34: 1-38. – (1994): Orginizing modernity, Oxford, Blackwell.

López, D., 2006, Home telecare as an extitution. Analysis of the new spatial forms of care. In F. J. Tirado & M. Domènech (Eds.), Lo social y lo virtual : Nuevas formas de control y transformación social (pp. 60-78). Barcelona: Editorial UOC.

Latour, B., 1997, “On Actor-Network Theory. A few clarifications. Published by the Centre for Social Theory and Technology, Keele University at: <http://www.keele.ac.uk/depts/stt/stt/ant/latour.htm>.

Serres, M., 1995, Atlas. Madrid: Cátedra

Serres, M., 1996, La comunicación : Hermes I. Barcelona: Anthropos Editorial del hombre.

Tirado, F. J., & Domènech, M., 2001, Extitutions: Of power and its anatomies. Politics and Society, 36, 183-196

Post a comment