Domenico Di Siena on the Dynamics of Collective Intelligence

A year ago, I received an invitation from Amalio Rey to answer a series of questions about Collective Intelligence, on the occasion of a research project that Amalio is developing for a book on this fascinating subject. The exchange was very interesting and resulted in a post that Amalio published about 8 months ago on his blog about Collective Intelligence.

I want to thank Amalio for his interest in my opinion and especially for his fantastic work in editing the interview text, which now allows me to have very valuable documentation of my thoughts on processes of Collective Intelligence. I hope you enjoy it.

Here is the text with the interview.

1. What successful examples of Collective Intelligence (CI) can you tell me about?

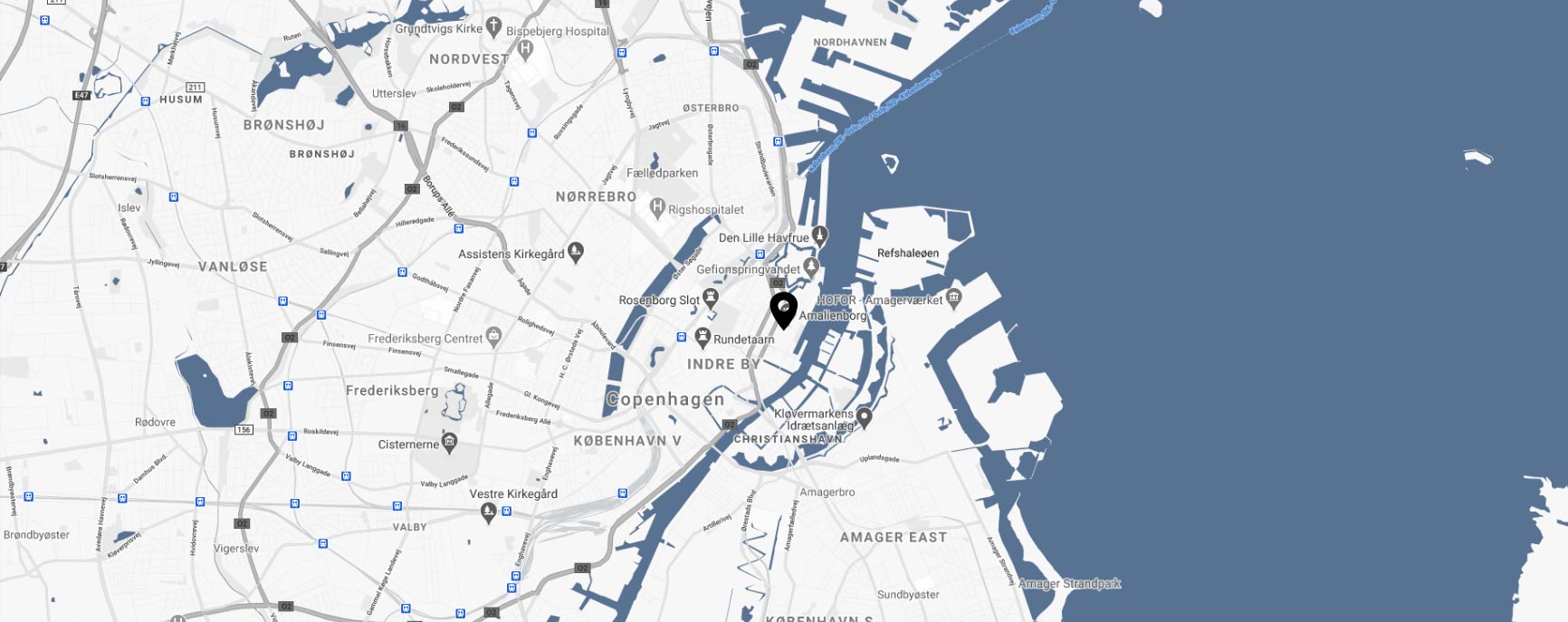

In Madrid, I have been fortunate to know different collective processes that have led to the creation of new quality urban spaces. Among them, El Campo de Cebada and Esta es una Plaza stand out. Both are the result of the collective and self-organized work of many people with governance based on an assembly system. The first is located in the very center of the city and has therefore achieved a metropolitan character. The second is in the Lavapiés neighborhood and is less known, so it retains a more local character.

It is interesting to reflect on some differences between the two. The management of the first, with its more metropolitan character, ends up being more difficult. The fundamental problem comes from the inability of the assembly managing the space to assume a type of visit that comes “from afar” and does not necessarily take responsibility for its maintenance. On weekends, this space is used by many people who are probably not fully aware of the management effort required. These visitors, surely recognize that it is a different space, especially for its unfinished character and continuous evolution. They surely recognize its “citizen” character, however, they end up using it with the same passive attitude they have in any other place in the city, where we are used to thinking that there is always someone who takes care of its maintenance. In the other initiative, “Esta es una Plaza,” however, the local character is much more evident and the space transmits from the beginning the existence of a community that takes care of it.

In the urban field, reflection on Collective Intelligence necessarily leads us to reflect on the relationship between the public, the common, and the private. In the examples I cited, the most problematic element is precisely in the dialectic that exists between the essence of a public space that is nevertheless managed by a community, even if it is done in an open and inclusive way.

2. Do you remember any failures and the reasons why they did not go well?

Personally, I have experienced several failures. I remember a project that in the end did not go ahead because we came together as people with personal affinities, but we lacked a shared vision. Fundamentally, our individual visions of the project were too different and the “commitment” to a common proposal moved too far away from each one’s objectives, so that no one really felt excited about the proposals that came out of the common construction. I think it is important for collective intelligence to agree on a shared goal or purpose as quickly as possible. Then it is quite likely that it will change, but it is precisely this common journey that makes it belong (emotionally) to the group. That is possible when everyone can recognize themselves in the starting point.

Another project followed a very simple idea: to get together to talk about pedagogical innovation. After the first meeting, no structure was defined, but it was agreed that each meeting would start from scratch, that there would be no predetermined topic or agenda, so that each new person who arrived would have the same “right” to propose topics. In addition, no rhythm of meetings was established, not even a fixed place. Everything was agreed directly online. I remember that in the last meetings a controversy was generated by the decision to open a Twitter account and a web page, which in fact never came to work. Everything had been absolutely distributed, so the opening of a Twitter account and a web page necessarily generated a centralization and a clear identity. In the last meetings, fewer and fewer people participated and the reason was, in my opinion, that the purpose of discussing new pedagogies had been exhausted, but the great personal synergies we had generated made us meet in other contexts, and even start new projects together. We lost interest in the meetings because we found something more valuable: the people. Quite a few projects and synergies were born and consolidated thanks to those meetings.

3. What factors determine, in your opinion, that a group is more collectively intelligent?

It is difficult to define some variables. Let’s see, the first thing I see as fundamental is the ability of each person to understand Collective Intelligence, or any collective project, as a learning process. Another is the purpose. If it is not clear from the beginning, or if a consensus on the purpose is not quickly achieved, it is more likely

that the process will not develop well.

Also influential is the capacity for collaboration, which we could understand as “collaborative intelligence” associated with network awareness. This has some relationship with “emotional intelligence,” and therefore with empathy. Intuitively I would say that an empathic person usually has good collaborative intelligence. But in reality it is difficult for people to understand that there is no absolute truth, so each person assumes that their proposal is the best of all. However, this is not how these processes are built. Each participant should see their idea as a brick made available to everyone to continue reflecting together, rather than a point of arrival.

4. When can a collective decision be considered “stupid”? How would you define “collective stupidity”?

Defining collective stupidity is just as difficult, or even more so, than collective intelligence. For me, it can be that process in which the participants are not creating anything new together, but simply conforming to the idea or proposal that seems to be shared by the majority. It has to do with a certain situation of comfort that prevents advancing collectively. If nothing new is created that did not exist before we came together, it seems to me a stupid process.

First of all, I have my doubts about whether the filter should be put on the result, or rather on the method or process followed. Often those results that seem stupid, because as you usually say “go against the group’s own interests,” have not been generated by truly collective dynamics, but consist of choosing between options created by others. Therefore, for me, it is the method that matters; so collective stupidity occurs when a group is not able to build its own universe of options.

This connects with the imaginary we have about how to reach collective solutions. In this sense perhaps our main reference is the democratic model. In fact, collective intelligence is often confused with democracy, forgetting that in a voting process by majorities vs. minorities we are not collectively creating anything new, but choosing between options that were already known.

5. There seem to be few successful cases of IC based on large-scale collaboration, and those that exist are always the same (Wikipedia, Linux, etc.). This leads me to wonder if that lack responds to a structural failure, to the fact that it is probably not viable due to the high coordination costs involved: what do you think?

Of course, I believe in the possibility of large-scale collaboration. It is more possible if the instigation process is not centralized and develops in a network, in a distributed way. For me, a clear example is the movement of occupations of the squares in Spain in May 2011, which ended up materializing in what we have called the #15m. The magic of distributed propagation is that it allows anyone to join with their own point of view, and invent the way they want to collaborate.

I think one of the problems comes from confusing networks and communities. If in a large-scale project you intend to generate a solid community, around a brand or identity, that usually generates tension with the idea that people feel really autonomous. A “community” requires an enormous amount of coordination work, which grows exponentially with the increase in the number of participants. A “network,” on the other hand, works in a more lax way, there is no need for so much coordination, although a good information infrastructure is needed.

When I belong to a Community, I also participate and accept a common identity that I can hardly contribute to changing. However, in a Network ecosystem, I do not have to wait for anyone’s authorization, I am always authorized to do so, the only thing I have to achieve is enough support within the network for it to be a collective process and then for it to be assumed by the rest of the participants.

In a Community process, a passive attitude is promoted, where spontaneously all its members tend to avoid confrontations or positions far removed from the positioning of the majorities. In more networked and distributed processes, a more open atmosphere is generated where divergence is not seen as something so problematic.

The Linux model gives many clues as to how a truly distributed model can work. It is about generating connected and independent nodes that work and row in the same direction. So far this model is not very widespread, but technologies like Blockchain are beginning to appear that can facilitate this way of working.

6. In the context of networks with the more relaxed functioning you propose, how is the perception of a collective identity or consciousness constructed?

I find it interesting to emphasize the role of collective opinion (distinct from Collective Intelligence) and how to overcome its supposed legitimizing weight. Our coexistence ecosystem is based on the perception of collective/public opinion as an agent of reality. That is, our relationship with others, and the territories we inhabit, has a lot to do with what we believe is the vision of others, in addition to our own. In other words, we create a reality based on what we think others think about it, and here, major media outlets (as well as social networks and the Internet) have a huge influence.

Therefore, all reflection on Collective Intelligence requires a change of context where direct value can be given to action, and therefore we should have a civic infrastructure less dependent on representatives and representational mechanisms. Ultimately, it’s about detaching creativity and innovation from the complicated processes of personal and collective legitimacy.

A fundamental problem is the inability to associate Participation with Empowerment and Co-responsibility. Even when Crowdsourcing is involved, these are processes where there is a responsible center and a participating periphery, without taking responsibility for the decisions and management. It’s a cultural and structural problem of society. Moving to take responsibility for things that society has taught us to consider the responsibility of others, or everyone which ultimately is nobody’s, is a very complicated process.

We should forget about referencing democratic ethics and consider more the hacker and anarchist ethics. I’m referring to the ability to generate a balance between the structuring action that may be promoted by representative institutions, and the action of participants who do not necessarily see themselves as represented or belonging to them.

7. Some complain, not without reason, that collective consultations often generate predictable solutions, and even a certain mediocre flattening of ideas as if they tend to “level down.” Do you agree with that? Is radical innovation incompatible with Collective Intelligence?

Indeed, I understand that Collective Intelligence can generate leveling dynamics, something that occurs especially when situations of aggregation around majority positions start to happen, leaving no space for the new and different which is considered “problematic” just because it could distance the group from the equilibrium found around the majorities. In fact, we know that in democracy when there is a perception that things are going well, the majority never opts for more radical proposals.

Returning to the idea that Collective Stupidity depends on how the process is developed, I would say the same here, that is, the non-innovative nature of Collective Intelligence also depends on this, on the followed mechanism. A process of Collective Intelligence can be totally minority and yet be totally legitimate. Hacker ethics is a good example, where greater weight and responsibility are given to those who are active, as opposed to the passive, as long as the process remains open, inclusive, and transparent.

8. But I return to the question that has been on my mind for a while now, as I listen to you: What do we do with Collective Intelligence in large-scale decision-making processes, if we discard democratic logics? Aren’t we risking leading to an even worse scenario, full of manipulations?

I think the key point is precisely in the fact that for me, Collective Intelligence has very little to do with decision-making. I see it as a process prior to decision-making, which is a task more associated with governance. In Civicwise, in fact, we talk about “maturing decisions” instead of “making decisions.” What we seek with these Collective Intelligence logics is that decision-making does not come “cold,” regardless of the mechanism used afterwards to decide.

Perfect examples are the cases of the referendum in Colombia, Brexit, and now Catalonia. In all of them, a series of issues around a single decision has been simplified in a way I would say almost irresponsibly, which is also generating a process of Collective Stupidity, as I explained earlier, because it increases that attitude of people to join a “simplified” stance instead of feeling challenged to create something new collectively.

Of course, decisions always have to be made in the end, and for that, there are democratic structures. But first, conditions must be created to mature decisions and generate Collective Intelligence processes that serve to work through possible scenarios so that when a decision is made, it can be much more complex.

9. As you and I have discussed on other occasions, low levels of participation are often a problem in collective processes. For example, in public management projects that call on citizens, participation percentages are often frustrating: Why is it so low?

Perhaps the problem is that I do not consider classic “Citizen Participation” initiatives as Collective Intelligence processes. One explanation is that often these dynamics continue to seek democratic and representative legitimization, and I do not believe that Collective Intelligence can be a democratic process, nor based on representativeness. Perhaps it is worth clarifying that I am not saying that Collective Intelligence is antidemocratic, but that its logic has nothing to

do with the practices of democratic voting or legitimization through majorities.

I often encounter processes in which something is proposed to which one simply has to join, and that, in general, is already defined by others. There may be some possibility of influence on the decision, but in essence, the margin for change is so reduced that we continue to be in a situation of “subordinates.” Real transformation occurs when these processes have to do with collective creation, which returns to citizens the protagonism over the identity and life of the territory they inhabit.

The problem arises when we try to seek legitimacy through voting processes, without really relating them to contextualized “creation” processes. This is the case for many proposals from the so-called “change councils.” Certainly, the openness to participation they propose through web platforms where citizen projects are launched, voted on, and once selected, funded, is interesting. However, we must never forget the need to generate processes of collective creation/construction/transformation, beyond proposing and choosing. There is also a lack of more contextualization in the territory, with practices of collective learning and urban pedagogy.

For example, I find the work of the Madrid City Council very interesting, which is starting to promote much more hybrid participation processes, combining digital consultations with actions more focused on collective creation, such as the Experimenta Distrito, Madrid Escucha, or the newly launched Imagina Madrid programs, which for the first time in Spain, promote a collaborative rather than competitive contest approach.

You may also like

Does Public Space Change with the Rise of the Internet?

According to Giovanni Sartori, the factors and processes that shape a person and transform them into

Situated Collective Intelligence

Without a doubt, mine is a generation marked by new technologies, the generation of computers, the i

Globalization and Its Effects on Our Relationship with the Territory

Globalization has normalized a lifestyle detached from the local dimension, generating a disconnect

Post a comment